Ringside seat for crucial election in the Andes

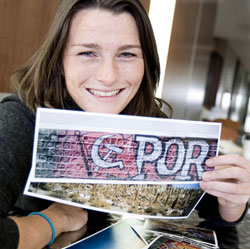

Giselle Murphy, a student who is completing her Master’s in Public Policy and Public Administration, shows some of her photos from Bolivia. Many show graffiti and murals that depict deep discontent with governance and the high levels of privatization there.

Photo by andrew dobrowolskyj

When the time comes for students in Concordia’s Master’s in Public Policy and Public Administration (MPPPA) program to do their internships, many take advantage of the program’s strong contacts on Parliament Hill.

Not Giselle Murphy. She spent the fall semester working at the Bolivian Centre for Multidisciplinary Studies. The non-profit institution studies issues facing Bolivia and the wider Andean region such as governance, indigenous rights and environmental management.

There, the political science student helped shape a proposal for a conservatory to facilitate links between NGOs in the Andes and in Canada.

“I’ve always been interested in Bolivia, which is the poorest country in South America,” Murphy said.

With the assistance of Eve Pankovitch, the program’s Internship Coordinator, Murphy became one of the first students in Canada to benefit from the Canada Corps initiative.

Administered by the Canadian International Development Agency, it gives eligible students up to $13,000 to travel abroad to study governance practices.

While in Bolivia, Murphy witnessed a turning point in the country’s history: the election of its first indigenous president, Evo Morales. She said the pre-election period was marked by rioting and civil unrest.

“People there are fighting against the neo-liberal policies of institutions like the World Bank and the IMF,” Murphy said.

“Eighty-five per cent of the Bolivian population is indigenous. They want a greater voice, and to nationalize resources that have been privatized, such as natural gas and water.

“With Morales in power, we hope they will have more of a voice,” she added. “Due to this privatization, they’ve got next to nothing.”

For example, Murphy said most Bolivians have limited access to potable water. The private companies are said to charge around US$300 to hook up homes to the water system, five times the monthly average Bolivian income of US$60 per month.

“This is why there’s poor sanitation and so much illness,” she said. She had food poisoning twice during her stay, including a bout with salmonella. She suspects she got it from eating unwashed vegetables.

She also had to adjust to the high altitude. At its highest point, Montreal is about 40 metres above sea level; La Paz is 3,800. “It was very trying physically. You can’t digest your food as well at high altitudes, and you always feel tired.”

Although she had taken intensive Spanish lessons before in Guatemala, Murphy polished her language skills with a tutor while there. She travelled on weekends, and squeezed in salsa lessons and volunteer work at a children’s shelter once a week.

“The people there are so welcoming and curious, that’s what really made this such a dynamic experience for me,” Murphy said. “It was so amazing to watch this country in transition.”

Murphy is now writing her internship report. She graduates this spring, and has her sights set on a career where she can continue to pursue her passion for Latin American culture and politics.