Energy in enzymes

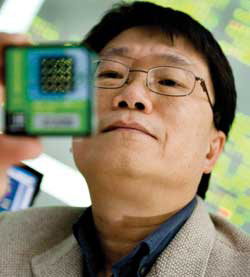

Dr. Adrian Tsang inspects a chip that allows him to determine the quantity and quality of DNA samples within minutes. This relatively new technology is only one example of several employed at Concordia’s Centre for Structural and Functional Genomics. The original method of separating DNA was developed in the 1970s, and takes six hours to complete.

Photo by andrew dobrowolskyj

You could say that Dr. Adrian Tsang is an alchemist. He doesn’t turn lead into gold, but says he could do the equivalent for motorists fed up with high gas prices: Turn organic waste into fuel.

“At least 40 per cent of our garbage is recoverable and can be used to produce fuels, energy, plastics and so forth. It’s a question of developing the technology to do so.”

Tsang is the principal researcher at Concordia’s Centre for Structural and Functional Genomics, and leads a national research team that is studying how fungal enzymes can be used to produce everything from chemical-free cleaning agents and food preservatives to fuel alternatives.

Fungi are nature’s top decomposers, Tsang said, and the enzymes they use to process their cellulose-laden diet are useful to attack clothing stains, whiten paper or even improve the texture and longevity of bread: 100 per cent naturally.

Since starting his research four years ago with the assistance of $7.5 million from Genome Canada and Génome Québec, Tsang said the team has focused its efforts on 15 particular species of mushrooms.

Once the secrets of their DNA are unraveled — and the recipes for their enzymes revealed — Tsang said the next step is to use that information in “cell factories,” which can produce the enzymes on the massive scale required for industrial use.

“We have identified over 2,000 unique enzymes that could have potential industrial applications,” he said. Some of these could assist in the production of bioethanol, a cleaner fuel alternative.

Fuel ethanol, is currently fermented from starch-based materials such as corn, barley or potatoes. “The problem is that we simply don’t have enough land to grow these on,” Tsang said.

Bioethanol could be manufactured by using a cocktail of fungal enzymes to decompose agricultural waste, such as corn husks, or organic residues, such as garbage, that don’t require land, irrigation or fertilizer.

The Canadian forestry industry alone produces 38.4 million tons of potentially usable waste every year, such as twigs, branches and leaves, Tsang said.

“With this waste alone, you could produce nearly five billion litres of bioethanol.”

He said it’s ironic that people are willing to pay more for a litre of bottled water — much of which comes from city water supplies — than they are for a litre of gas, which is much more expensive to pull out of the ground and process.

“Gas is a very cheap commodity because it’s so abundant right now. But it won’t last forever.”