Viewing consumers through Darwinian lens

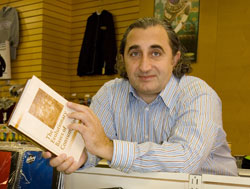

Gad Saad (Marketing) explains our consumer preferences as a function of evolutionary theory.

linda rutenberg

Marketing professor Gad Saad believes that many consumption patterns, from the foods we eat to the gifts we offer and the cultural products we enjoy, are intimately related to our biological heritage.

His new book, The Evolutionary Bases of Consumption, uses Darwinian theory, including natural and sexual selection, to map our consumer choices.

“In the book, I define the term ‘consumption’ in a much grander sense than most people in the field do,” Saad said in an interview. “For example, we ‘consume’ friends, mates, religious narratives and products of popular culture.”

He traces his research back to a course he took as a doctoral student at Cornell. The course introduced him to evolutionary psychology. “I had an epiphany when I considered how powerfully this operated on every biological organism.”

For instance, the survival module considers how humans have evolved in terms of natural selection. “Our taste preferences are an adaptation to caloric scarcity and caloric uncertainty. This is why we seek out fatty and sweet foods,” Saad said, tracing a trail directly to McDonald’s golden arches.

“McDonald’s preeminence [in global markets] is minimally due to its advertising campaigns. These may remind you to walk in, but once you’re there, it’s the evolved preference for fatty foods that will keep you there.”

Saad describes how many consumer choices are forms of sexual signaling relevant in the mating arena. “A lek is a physical space where males typically compete for female attention across a wide range of species.

“If you go to Crescent St. any night of the week, you’ll see men driving around the block for four hours to show off their cars. They are engaging in sexual signalling not unlike the male peacock, who shows off his extravagant ornaments. In this sense, Crescent St. is a lek.”

The book suggests that advertising does not form consumer preferences. Instead, it typically mirrors our evolved human nature. That said, Saad addresses advertising campaigns that seem to challenge his theory, notably the Dove soap campaign, which denies the existence of universal standards of beauty (or ‘success,’ in mating/reproducing terms).

“Dove is saying, ‘Hey, ladies, beauty is a social construction.’ It’s smart marketing that makes everyone feel equally worthy in the mating game.”

Saad’s book explains gambling addictions and eating disorders through his evolutionary framework. “This is the dark side of consumption,” he said.

“These consumption acts are maladaptive outcomes rooted in an otherwise adaptive mechanism. Their morbidity occurs in a universal, sex-specific way.

“For example, women constitute 90 per cent of those suffering from eating disorders and compulsive buying, whereas the large majority of those suffering from gambling and pornographic addictions are men. These universal patterns are rooted in a Darwinian etiology.”

Saad does not say that biology is entirely destiny. He recognizes that these patterns are part of a bigger picture of other relevant forces, including environmental influences and life experiences. But he does not think they should be denied, either.

“In the social sciences, there is an argument that we transcend our biology with culture. Natural scientists are perplexed by this position.

“Much of our culture arises out of our biological heritage. Consumption cannot be fully understood without a recognition that consumers are biological beings shaped by evolutionary forces.”