Concordia Corner

State of the (fine) art is a techie playground

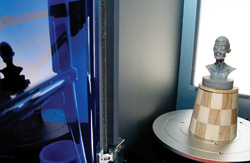

Students can use the 3D scanner to produce layered prototypes of objects.

Photo by Rob Maguire

Mich Sardella (Administrator, Design and Computation Arts) said that when most of the Fine Arts Faculty moved into new facilities in the EV Building, “the idea was to come together,” both professionally and physically.

One of the unifying steps was to integrate shared technical space for both the studio and design arts programs. The massive facility, which takes up a good part of the EV eighth floor, is called the Visual Arts Technical Centre or VATC.

VATC contains everything students and faculty could ever need to build with and manipulate wood, metal and plastics.

In the wood rooms, there are hand tools, as well as table saws, lathes, routers and a vented area for sanding. There’s even a CNC milling machine run by computer.

Senior Technician Andrzej Krysztofowicz explained that students prepare their designs in AutoCAD, then mount wood or plastic into the machine that cuts shapes to exacting specifications. One student produced a magazine rack where wooden dowels fit so precisely in their holes that “they can’t be budged.”

The metal rooms contain high-tech machinery for cutting, welding, molding and bending metal into any shape imaginable. Again, many machines are linked to computers for precision and repeat operations.

Then there is the Rapid Prototyping Room (RPR), which Krysztofowicz called “the highest end of fine arts facilities ever, at least in terms of technology.”

At first glance, the RPR doesn’t look nearly as interesting as the wood or metal working areas. It’s a plain white room with a tile floor and a few boxlike machines sitting around on counter tops. The most interesting-looking item is a mechanical arm.

“It allows for 3D scanning of fairly large objects,” Krysztofowicz explained. The arm is linked to a computer that can measure the precise position of the sensor at its tip. Users draw a grid on the surface of the object to be scanned, then touch the sensor to key points on the grid. The computer tracks each point, creating a digital map from the changes in position between adjacent points. The resulting image is a 3D wireframe model that can be manipulated with programs like Form Z, Maya or 3D Studio.

With smaller objects, the scanning process is even simpler. The object is simply placed inside the 3D laser scanner, and scanned at the push of a button.

When these two machines are paired with the 3D printer expected early this year, users will be able to scan an object, change it and then print the new three dimensional prototype in layers of plastic or starch.

While the potential uses raise interesting questions about copyright issues, Krysztofowicz is thrilled with the technology and its capabilities. “It’s the ultimate in reverse engineering,” he said, “and the engineers wish they had one, ”