Gisele Amantea draws on the past

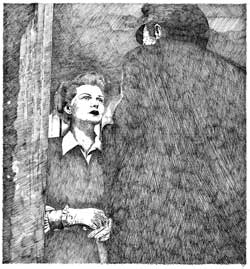

Gisele Amantea’s drawing captures the spirit of prohibition filtered through iconic images of film noir.

images courtesy of Gisele Amantea

During the Roaring Twenties, most of Canada respected Prohibition, flappers were raising eyebrows and hemlines, and despite having decades-old communities established across the country, Italians were still feared as swarthy, dangerous immigrants.

All of these elements are important to the story of The King v. Picariello and Lassandro. Studio Arts professor Gisele Amantea has literally pieced together this bit of history in a series of drawings based on letters, family and archival photographs, news clippings and court documents. First incorporated in a series of large-scale prints displayed in the Regina Public Library’s Dunlop Art Gallery, the drawings are now the basis of a video and book which were recently launched at Groupe Intervention Vidéo.

The facts of the story are simple. Stephen O. Lawson was a member of the police force charged with keeping Alberta dry, i.e. alcohol-free. Stationed in Coleman in the coal-mining region of Crowsnest Pass in southwestern Alberta, he wounded bootlegger Emilio Picariello’s son, Stefano, who was fleeing in a car full of illegal liquor. Emilio and Florence Lassandro travelled from their nearby town to confront Lawson. The police officer was shot and Lassandro and Picariello were ultimately hanged for his murder.

Amantea remembers driving through the area as a child. “It was really rough, very poor, but also very beautiful.” The story is one she heard often from her own father, who although much younger than the accused, grew up in the same small Italian community. “The families knew each other.”

The book was published by the Frank Iacobucci Centre for Italian Canadian Studies, University of Toronto Press.

When she returned to the area in 1999, she was struck by how the story had been reinterpreted as a tourist attraction, “with restaurants named after Picariello and their images on the side of buildings.” Tourism Alberta has published several books, and there was an opera, produced in 2003.

However, Amantea felt that the story of immigrants in an economically depressed mining community that had not wanted to go dry for Prohibition had gotten lost in the retelling.

Lassandro herself had come to Canada as a child with the name Filumena Constanza. Her life changed when she was married off to a man 10 years her senior. Most of the popular versions of her story have created a romantic relationship between her and Stefano, “but Florence was more innocent than that,” insists Amantea. She sees Lassandro’s story as having been bent to fit the role of the evil femme fatale, an easy enough transposition, since “there is very little left of Florence” and no record of her perspective on events.

In fact, the popular imagination, in film depictions of Prohibition, served as a model for many of the drawings in Amantea’s work. By refashioning the protagonists as Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney and Faye Dunaway in classic movie-still poses, Amantea forces us to reflect on how such stories are “filtered through our cultural imagination, reinterpreted through the great tradition of noir and pulp cinema, which was in its turn inspired by real-life crime,” according to Luca Somigli, of the University of Toronto, who has written the introduction to Amantea’s book.

The story blends fact and an awareness of fiction through “private story, public history, and cultural imagination,” he continues.

Amantea’s layers of headlines and transcripts help us to uncover the racism of the period. The final clipping from Toronto’s Tribuna Canadiana points out, in Italian, that not a single English woman had been executed in the country in two dozen years.

Amantea said that the nearly century-old story still finds echoes in popular culture through the members of the Soprano family. However, in her acknowledgments, Amantea points out that “cultural stereotypes concerning immigration and race continue to be a source of bias and discrimination” over successive generations of newcomers.