Canadian cinema comes out

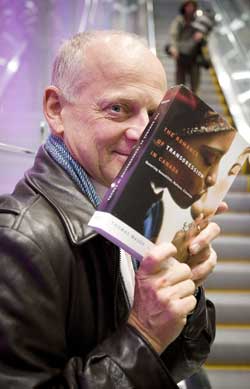

Tom Waugh presents his guide to Canadian queer cinema and video.

photo by andrew dobrowolskyj

Sometimes bigger is better. So when Tom Waugh (Cinema) launched what has immediately been recognized as the definitive compendium on Canadian queer cinema and video, a companion panel discussion and lecture seemed appropriate warm ups for the main event.

Timing his book launch with the 18th edition of Montreal’s queer film festival, Image + Nation, begged the question of whether the festival was celebrating the book, or the book the festival.

It is hard to describe a 600-page opus which catalogues Waugh’s exhaustive knowledge of the evolution of queer cinema in a series of essays along with a minutely researched who’s who of Canada’s cinema and video producers whose work fits into his notion of queer. Panelists at the Nov. 18 event to launch The Romance of Transgression in Canada: Queering Sexualities, Nations, Cinemas simply referenced the work as ‘the bible.”

“Though the King James version actually comes in at a few less pages,” John Greyson (Lilies) joked.

Waugh himself acknowledged that the work, which covers over 60 years, was extremely ambitious. “If I’d have known how big it was, and how vital, I don’t think I would have started.”

Greyson was joined by Patricia Rozema (When Night is Falling), Michel Langlois (Le fil cassé) and local video artists Dayna McLeod and Anne Golden, on a panel chaired by Chantal Nadeau (Communication Studies). All the panelists addressed the impact of Waugh’s work and the larger question of transgression in Canadian cinema and culture.

“I used to think that simply putting this work on screens so that other people could come out to see it was transgressive,” said Golden, discussing her role as an organizer during the early years of Image + Nation. “Now I think the concept of ‘transgressive’ has migrated to the content.”

Certainly, as other panelists noted, an increasing number of mainstream films with decidedly queer themes (Monster, Brokeback Mountain, Boys Don’t Cry, The Hours, and two different explorations of Truman Capote) have made the notion of challenging conventions more complex.

Waugh chose to present Canadian film-makers’ exploration of the edgy in his lecture, prefaced with a quote by Canadian film reviewer Katherine Monk, “Canadian sex is really weird, dark and quirky. It’s impossible to find positive and normal images of Canadian sex.” Playing with that theme, Waugh showed a series of clips in his lecture, addressing that question from the perspective of student films right to mainstream features, with numerous detours in between.

For Greyson, the value of Waugh’s intervention is “his commitment to transgressing borders of every sort.” He commented on Waugh’s ability to situate Canadian trends within larger international movements.

Waugh argued that at a time when same-sex marriage has become the Canadian norm, “Canada is involved in a romance, not of the conjugal kind, but what I call the romance of transgression.” With no Hollywood studio centre, a small national audience compared to the production houses down south, and no promise of screens outside of annual festivals and art houses, many of Canada’s queer cineastes “are doing it on the fly.”